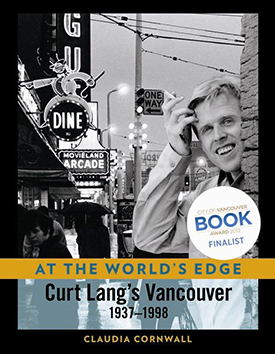

I find a long-lost film-maker, a long-lost painting and (maybe) a treasure trove of Vancouver’s beat history

Writing a book is a little like having a child. The child grows up, ventures out into the world and does all sorts of things that surprise you. I was reminded of this quite vividly when I unexpectedly received an email from PG Forest. He introduced himself by saying that his father was Leonard Forest, who directed a National Film Board documentary in which Curt Lang briefly appears. PG Forest lived in Montreal but wrote that he would be visiting Vancouver for a few days and wondered if we could chat. Of course I was curious and suggested we meet for coffee.

I knew exactly which film he meant—In Search of Innocence, a haunting movie about artists, writers and musicians in beat-era Vancouver. Leonard Forest, an Acadian and the director of French programming at the NFB, made the film about 1964. (There’s a French version too, called À la recherche de l’innocence).

When I was working on At the World’s Edge, I tried to find Leonard Forest, because I had heard some interesting stories about the making of his film. They give you a sense of some of the difficulties associated with tackling such an edgy subject. Curt’s friend, the artist Fred Douglas, who is also in the film, got so drunk that he fell asleep in his car, and as a consequence, the shooting of a scene with him had to be postponed until another day. I was eager to hear more about how and why the film was made, so I began looking for the director. I called the National Film Board in Montreal where Forest had been involved in the production of about 130 films from 1953 until 1980. I was told to try the NFB regional office in New Brunswick. A couple of emails later, I learned that Forest lived in Moncton and I found someone who knew him. Unfortunately, I also found out that he was too ill to speak to speak to me. Even so, I mentioned the film in my book. Naturally I was disappointed that I was not able to do the interview, but I shrugged off the experience as a line of inquiry that didn’t work out. Perhaps I was wrong though. Maybe now I would get to pursue it after all.

I met PG Forest at his hotel in Coal Harbour. He told me I would be able to recognize him because he would be the person in the lobby reading At the World’s Edge. And sure enough he was—a well dressed man in his fifties with short grey hair. To talk, we went to a coffee shop just a few blocks away from where Curt and Fred Douglas had shared disreputable digs. As the afternoon sun played over the Northshore peaks, I told Forest that that his father’s film was legendary in Vancouver—one of the few pieces of documentation about the beats here. It contains rare footage of The Cellar, the jazz club which flourished for a number of years on East Broadway after its debut in 1955. The movie’s innovative score was written and performed by the Al Neil trio. And in it, you see many icons of the time—Jack Shadbolt and Don Jarvis working on their paintings, Roy Kiyooka, teacher and artist, in conversation about the meaning of the word “spontaneity,” Fred Douglas reading passionately from a notebook. Interspersed between the paintings and the talk are scenes of the city—a running sea, logs strewn over a beach, fishing boats, freighters in the mist, a dark checkerboard of electrical cables over an alley. Since I have lived in Vancouver almost all my life, these sights were familiar, but still there’s something about the film that makes the city seem almost like a place out of time. Forest said, “For my father, Vancouver was at the end of the line.” Perhaps that’s why the film had this unusual quality. I also told Forest that I had tried to find his father when I was writing my book, but had discovered that he was too ill to talk to me. “He’s better now,” he said. “His voice has recovered.”

PG Forest explained that he did not follow in his father’s footsteps. For many years a professor of public policy at the University of Laval, he was also the director of research on the Romanow Commission. (It was Roy Romanow who started calling him PG instead of Pierre-Gerlier and it stuck.) Today PG Forest is the president of the Pierre Trudeau Foundation, an organization that supports research in the humanities and the social sciences. I found that he took a keen interest in art and cinema. He told me that his father’s film owes much to the French New Wave of cinema, a style popular in the late fifties and sixties. I always thought its dreamlike mood, the collage of juxtaposed scenes, the lack of narrative arc, was inspired by Vancouver itself. But PG told me it grew out of Leonard’s exposure to the new directions moviemakers were exploring in Paris. Leonard had taken his family to France and spent three years immersing himself in the innovative French style. He worked for René Clair who was awarded the Grand Prix du Cinéma Français in 1953. Just a few months after returning to Canada, Leonard went to Vancouver to make In Search of Innocence. It was the first Canadian film he made after his European apprenticeship. You see Vancouver, but through a French lens.

New Wave films were often shot on a low budget. The directors would use acquaintances as actors and the location would be a friend’s apartment. Forest was under a tight budget too. To save money, he used colour sparingly, mostly to film the paintings he featured. Everything else was in black and white. Like other New Wave directors, he used a hand-held camera, whose aesthetic potential was just starting to be exploited. According to Wikipedia, New Wave “filming techniques included fragmented, discontinuous editing, and long takes. The combination of objective realism, subjective realism, and authorial commentary created a narrative ambiguity in the sense that questions that arise in a film are not answered in the end.” This does indeed sound a lot like In Search of Innocence.

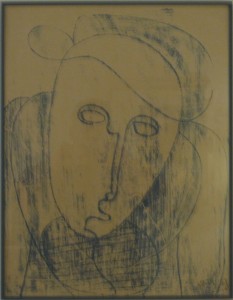

Leonard was not a cool observer; he was an active participant in the kind of culture the film portrayed. He also wrote essays and poetry and his poetic sensibility is evident in the voice-overs. Vancouver he says “is the end of something and the beginning of something.” It is, he maintains, “the unfinished city.” PG Forest told me that when his father came to Vancouver to make the film, he bought pieces from the artists he was interviewing. (In fact it was these pieces of art that led PG to look for me. He wanted to find out more about them, and so discovered my books.) Leonard bought prints and a sculpture from Jack Hardman. (I wrote about him in The Life and Art of Frank Molnar, Jack Hardman, and LeRoy Jensen.) Leonard also bought a couple of pictures PG surmised were Curt’s. The signature was indistinct but you can just make out what looks like “Lang.”

I was astonished—these were rare artifacts indeed—a valuable addition to the known Curt Lang artistic “oeuvre!” Don MacLeod, the bookseller, had given me one oil painting of Curt’s (dragged out from storage in a shed) and Fred Douglas’s daughter Lisa showed me two. This was all I was able to discover, in spite of the fact that in the early sixties, Curt was regarded as part of the artistic avant-garde. His work was in a show in the Vancouver Art Gallery in March 1960 and in another one in the New Design Gallery in April 1960.

PG Forest also told me that when his father made a film, he was usually thorough about documenting the creation. He took many still photographs, recorded interviews, and made careful notes. PG said “I wouldn’t be surprised if there were a couple of boxes of material like this about In Search of Innocence.” I was intrigued. Was there really such a box? Was a treasure trove of beat culture now sitting in Moncton, perhaps untouched for many years? What could I find there? What insights would I glean from the contents? And then I thought of something else.

“Why do you think your father made the film? What brought him to Vancouver?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” PG said. “It was the only trip he ever made out here.”

“Do you think he would talk to me now?”

“Perhaps,” he said. “I will visit my father in January. I’ll try to persuade him.”

To be continued.

So what happened Claudia? Did you find Len Forest?

Hi Judith,

Sorry it has taken me so long to realize you made a comment! I have not spoken to Len. He is apparently a recluse of sorts, grumpy, a “difficult” man. PG wanted to get his father to send his box of documentation about “In Search of Innocence” out here, where it would have more meaning than in Moncton. But I don’t think he was able to get his father to do that. But you have reminded me of my enthusiasm about this, I’ll try to find out if there is any possibility of further developments!